Key Points

-

Although African, Caribbean and African-American populations are all groups of African descent, cultural and historical differences mean that strategies for the diagnosis and prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in each population require customization

-

In Africa, as T2DM occurs across the entire range of BMIs, enrolment criteria for both screening and prevention trials must consider that even normal-weight African individuals are at risk

-

Both Caribbean and African-American individuals have experienced the twin epidemics of obesity and T2DM; however, Caribbean individuals seem to have worse glycaemic control, lower health literacy and a higher rate of complications

-

When intensive lifestyle interventions are undertaken in Africa and the Caribbean, both the design and outcome must be appropriate for the specific African-descent population enrolled

-

Reducing the rate of undiagnosed T2DM in African-descent populations requires optimization of current screening tests by combining HbA1c with fasting plasma glucose and evaluating new tests such as glycated albumin

-

Large studies are necessary in African-descent populations to identify the risk of T2DM due to genetics, epigenetics and gene–environment interactions

Abstract

Populations of African descent are at the forefront of the worldwide epidemic of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The burden of T2DM is amplified by diagnosis after preventable complications of the disease have occurred. Earlier detection would result in a reduction in undiagnosed T2DM, more accurate statistics, more informed resource allocation and better health. An underappreciated factor contributing to undiagnosed T2DM in populations of African descent is that screening tests for hyperglycaemia, specifically, fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c, perform sub-optimally in these populations. To offset this problem, combining tests or adding glycated albumin (a nonfasting marker of glycaemia), might be the way forward. However, differences in diet, exercise, BMI, environment, gene–environment interactions and the prevalence of sickle cell trait mean that neither diagnostic tests nor interventions will be uniformly effective in individuals of African, Caribbean or African-American descent. Among these three populations of African descent, intensive lifestyle interventions have been reported in only the African-American population, in which they have been found to provide effective primary prevention of T2DM but not secondary prevention. Owing to a lack of health literacy and poor glycaemic control in Africa and the Caribbean, customized lifestyle interventions might achieve both secondary and primary prevention. Overall, diagnosis and prevention of T2DM requires innovative strategies that are sensitive to the diversity that exists within populations of African descent.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas — 7 th edition. IDF http://www.oedg.at/pdf/1606_IDF_Atlas_2015_UK.pdf (2015).

United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly: scope, modalities, format and organization of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. UN http://www.un.org/en/ga/president/65/issues/A-RES-65-238 (2011).

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. WHO http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf?ua=1 (2013).

American Diabetes Association. 10. Microvascular complications and foot care. Diabetes Care 40, S88–S98 (2017).

American Diabetes Association. 9. Cardiovascular disease and risk management. Diabetes Care 40, S75–S87 (2017).

Hennis, A., Wu, S. Y., Nemesure, B., Li, X. & Leske, M. C. Diabetes in a Caribbean population: epidemiological profile and implications. Int. J. Epidemiol. 31, 234–239 (2002).

Menke, A., Casagrande, S., Geiss, L. & Cowie, C. C. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 314, 1021–1029 (2015).

Commodore-Mensah, Y., Himmelfarb, C. D., Agyemang, C. & Sumner, A. E. Cardiometabolic health in African immigrants to the United States: a call to re-examine research on African-descent populations. Ethn. Dis. 25, 373–380 (2015).

Manne-Goehler, J. et al. Diabetes diagnosis and care in sub-Saharan Africa: pooled analysis of individual data from 12 countries. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 903–912 (2016).

Mbanya, J. C., Motala, A. A., Sobngwi, E., Assah, F. K. & Enoru, S. T. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 375, 2254–2266 (2010).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 387, 1513–1530 (2016).

Werfalli, M., Engel, M. E., Musekiwa, A., Kengne, A. P. & Levitt, N. S. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes among older people in Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 72–84 (2016).

Dabone, C., Delisle, H. & Receveur, O. Predisposing, facilitating and reinforcing factors of healthy and unhealthy food consumption in schoolchildren: a study in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Glob. Health Promot. 20, 68–77 (2013).

Igumbor, E. U. et al. “Big food,” the consumer food environment, health, and the policy response in South Africa. PLoS Med. 9, e1001253 (2012).

Keding, G. B., Msuya, J. M., Maass, B. L. & Krawinkel, M. B. Dietary patterns and nutritional health of women: the nutrition transition in rural Tanzania. Food Nutr. Bull. 32, 218–226 (2011).

Obirikorang, Y. et al. Knowledge and lifestyle-associated prevalence of obesity among newly diagnosed type II diabetes mellitus patients attending diabetic clinic at Komfo Anokye teaching hospital, Kumasi, Ghana: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 9759241 (2016).

Oyewole, O. E. & Atinmo, T. Nutrition transition and chronic diseases in Nigeria. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 74, 460–465 (2015).

Assah, F. K., Ekelund, U., Brage, S., Mbanya, J. C. & Wareham, N. J. Free-living physical activity energy expenditure is strongly related to glucose intolerance in Cameroonian adults independently of obesity. Diabetes Care 32, 367–369 (2009).

Assah, F. K., Ekelund, U., Brage, S., Mbanya, J. C. & Wareham, N. J. Urbanization, physical activity, and metabolic health in sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Care 34, 491–496 (2011).

Keding, G. Nutrition transition in rural Tanzania and Kenya. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 115, 68–81 (2016).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 387, 1377–1396 (2016).

Dagenais, G. R. et al. Variations in diabetes prevalence in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: results from the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology Study. Diabetes Care 39, 780–787 (2016).

O'Connor, M. Y. et al. Worse cardiometabolic health in African immigrant men than African American men: reconsideration of the healthy immigrant effect. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 12, 347–353 (2014).

Ukegbu, U. J. et al. Metabolic syndrome does not detect metabolic risk in African men living in the U.S. Diabetes Care 34, 2297–2299 (2011).

de Rooij, S. R., Roseboom, T. J. & Painter, R. C. Famines in the last 100 years: implications for diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 14, 536 (2014).

Hult, M. et al. Hypertension, diabetes and overweight: looming legacies of the Biafran famine. PLoS ONE 5, e13582 (2010).

van Abeelen, A. F. et al. Famine exposure in the young and the risk of type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes 61, 2255–2260 (2012).

UNICEF USA. Emergency relief: famine threatens 2.5 million children in Africa and the Middle East. UNICEF USA https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/famine-threatens-25-million-children-africa-and-middle-east/32005 (2017).

Sobngwi, E. et al. Ketosis-prone type 2 diabetes mellitus and human herpesvirus 8 infection in sub-Saharan Africans. JAMA 299, 2770–2776 (2008).

Boyne, M. S. Diabetes in the Caribbean: trouble in paradise. Insulin 4, 94–105 (2009).

Ferguson, T. S., Tulloch-Reid, M. K. & Wilks, R. J. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Jamaica and the Caribbean: a historical review. West Indian Med. J. 59, 259–264 (2010).

Boyne, M. S. et al. Energetic determinants of glucose tolerance status in Jamaican adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 58, 1666–1668 (2004).

Cunningham-Myrie, C. et al. Diabetes mellitus in Jamaica: sex differences in burden, risk factors, awareness, treatment and control in a developing country. Trop. Med. Int. Health 18, 1365–1378 (2013).

Wilks, R. et al. Diabetes in the Caribbean: results of a population survey from Spanish Town, Jamaica. Diabet. Med. 16, 875–883 (1999).

Howitt, C. et al. A cross-sectional study of physical activity and sedentary behaviours in a Caribbean population: combining objective and questionnaire data to guide future interventions. BMC Public Health 16, 1036 (2016).

Ragoobirsingh, D., Lewis-Fuller, E. & Morrison, E. Y. The Jamaican Diabetes Survey. A protocol for the Caribbean. Diabetes Care 18, 1277–1279 (1995).

Ferguson, T. S. et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease among patients attending a specialist diabetes clinic in Jamaica. West Indian Med. J. 64, 201–208 (2015).

Leske, M. C. et al. Nine-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy in the Barbados Eye Studies. Arch. Ophthalmol. 124, 250–255 (2006).

Hambleton, I. R. et al. All-cause mortality after diabetes-related amputation in Barbados: a prospective case-control study. Diabetes Care 32, 306–307 (2009).

Hennis, A. J., Fraser, H. S., Jonnalagadda, R., Fuller, J. & Chaturvedi, N. Explanations for the high risk of diabetes-related amputation in a Caribbean population of black african descent and potential for prevention. Diabetes Care 27, 2636–2641 (2004).

Gayle, K. A. et al. Foot care and footwear practices among patients attending a specialist diabetes clinic in Jamaica. Clin. Pract. 2, e85 (2012).

Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Ogden, C. L. & Johnson, C. L. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 288, 1723–1727 (2002).

Menke, A., Rust, K. F., Fradkin, J., Cheng, Y. J. & Cowie, C. C. Associations between trends in race/ethnicity, aging, and body mass index with diabetes prevalence in the United States: a series of cross-sectional studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 161, 328–335 (2014).

Kuczmarski, R. J., Flegal, K. M., Campbell, S. M. & Johnson, C. L. Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1960 to 1991. JAMA 272, 205–211 (1994).

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Kit, B. K. & Flegal, K. M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 311, 806–814 (2014).

Cowie, C. C. et al. Prevalence of diabetes and high risk for diabetes using A1C criteria in the U.S. population in 1988–2006. Diabetes Care 33, 562–568 (2010).

Cowie, C. C. et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care 29, 1263–1268 (2006).

Herman, W. H. & Rothberg, A. E. Prevalence of diabetes in the United States: a glimmer of hope? JAMA 314, 1005–1007 (2015).

Goldberg, J. B., Goodney, P. P., Cronenwett, J. L. & Baker, F. The effect of risk and race on lower extremity amputations among Medicare diabetic patients. J. Vasc. Surg. 56, 1663–1668 (2012).

Harris, M. I., Klein, R., Cowie, C. C., Rowland, M. & Byrd-Holt, D. D. Is the risk of diabetic retinopathy greater in non-Hispanic blacks and Mexican Americans than in non-Hispanic whites with type 2 diabetes? A U.S. population study. Diabetes Care 21, 1230–1235 (1998).

Sinha, S. K. et al. Association of race/ethnicity, inflammation, and albuminuria in patients with diabetes and early chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Care 37, 1060–1068 (2014).

Varma, R. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 132, 1334–1340 (2014).

Herman, W. H. et al. Early detection and treatment of type 2 diabetes reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality: a simulation of the results of the Anglo–Danish–Dutch study of intensive treatment in people with screen-detected diabetes in primary care (ADDITION-Europe). Diabetes Care 38, 1449–1455 (2015).

Balk, E. M. et al. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 437–451 (2015).

Schellenberg, E. S., Dryden, D. M., Vandermeer, B., Ha, C. & Korownyk, C. Lifestyle interventions for patients with and at risk for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 159, 543–551 (2013).

Knowler, W. C. et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002).

Wing, R. R. et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 145–154 (2013).

Keyserling, T. C. et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes: impact on physical activity. Diabetes Care 25, 1576–1583 (2002).

Mayer-Davis, E. J. et al. Pounds off with empowerment (POWER): a clinical trial of weight management strategies for black and white adults with diabetes who live in medically underserved rural communities. Am. J. Public Health 94, 1736–1742 (2004).

Samuel-Hodge, C. D. et al. Family PArtners in Lifestyle Support (PALS): family-based weight loss for African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 25, 45–55 (2017).

Samuel-Hodge, C. D. et al. A randomized trial of a church-based diabetes self-management program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 35, 439–454 (2009).

Haffner, S. M., Stern, M. P., Hazuda, H. P., Mitchell, B. D. & Patterson, J. K. Cardiovascular risk factors in confirmed prediabetic individuals. Does the clock for coronary heart disease start ticking before the onset of clinical diabetes? JAMA 263, 2893–2898 (1990).

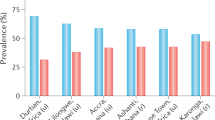

Cooper, R. S. et al. Prevalence of NIDDM among populations of the African diaspora. Diabetes Care 20, 343–348 (1997).

Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B., Mayige, M., Ogbera, A. O., Sobngwi, E. & Kengne, A. P. Screening for hyperglycemia in the developing world: rationale, challenges and opportunities. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 98, 199–208 (2012).

Barry, E. et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of screen and treat policies in prevention of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of screening tests and interventions. BMJ 356, i6538 (2017).

Davidson, M. B. & Pan, D. Epidemiological ramifications of diagnosing diabetes with HbA1c levels. J. Diabetes Complications 28, 464–469 (2014).

Levitt, N. S. et al. Application of the new ADA criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes to population studies in sub-Saharan Africa. Diabet. Med. 17, 381–385 (2000).

Motala, A. A., Esterhuizen, T., Gouws, E., Pirie, F. J. & Omar, M. A. Diabetes and other disorders of glycemia in a rural South African community: prevalence and associated risk factors. Diabetes Care 31, 1783–1788 (2008).

Sumner, A. E. et al. Detection of abnormal glucose tolerance in Africans is improved by combining A1C with fasting glucose: the Africans in America Study. Diabetes Care 38, 213–219 (2015).

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 40, S11–S24 (2017).

[No authors listed.] Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 28, 1039–1057 (1979).

Colagiuri, S. et al. Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care 34, 145–150 (2011).

Weyer, C., Bogardus, C. & Pratley, R. E. Metabolic characteristics of individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 48, 2197–2203 (1999).

[No authors listed.] Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 20, 1183–1197 (1997).

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 27, S5–S10 (2004).

[No authors listed.] Summary of revisions for the 2010 Clinical Practice Recommendations. Diabetes Care 33, S3 (2010).

Gillett, M. J. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes: Diabetes Care 2009; 32(7): 1327–1334. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 30, 197–200 (2009).

Chung, S. T., Chacko, S. K., Sunehag, A. L. & Haymond, M. W. Measurements of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis: a methodological review. Diabetes 64, 3996–4010 (2015).

DeLany, J. P. et al. Racial differences in peripheral insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial capacity in the absence of obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 4307–4314 (2014).

Ellis, A. C., Alvarez, J. A., Granger, W. M., Ovalle, F. & Gower, B. A. Ethnic differences in glucose disposal, hepatic insulin sensitivity, and endogenous glucose production among African American and European American women. Metabolism 61, 634–640 (2012).

Goedecke, J. H. et al. Ethnic differences in hepatic and systemic insulin sensitivity and their associated determinants in obese black and white South African women. Diabetologia 58, 2647–2652 (2015).

Osei, K., Cottrell, D. A. & Harris, B. Differences in basal and poststimulation glucose homeostasis in nondiabetic first degree relatives of black and white patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 75, 82–86 (1992).

Guerrero, R., Vega, G. L., Grundy, S. M. & Browning, J. D. Ethnic differences in hepatic steatosis: an insulin resistance paradox? Hepatology 49, 791–801 (2009).

Samuel, V. T. & Shulman, G. I. The pathogenesis of insulin resistance: integrating signaling pathways and substrate flux. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 12–22 (2016).

Bianchi, C. et al. Pathogenetic mechanisms and cardiovascular risk: differences between HbA1c and oral glucose tolerance test for the diagnosis of glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 35, 2607–2612 (2012).

Lorenzo, C. et al. A1C between 5.7 and 6.4% as a marker for identifying pre-diabetes, insulin sensitivity and secretion, and cardiovascular risk factors: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Diabetes Care 33, 2104–2109 (2010).

Olson, D. E. et al. Screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes with proposed A1C-based diagnostic criteria. Diabetes Care 33, 2184–2189 (2010).

English, E. et al. The effect of anaemia and abnormalities of erythrocyte indices on HbA1c analysis: a systematic review. Diabetologia 58, 1409–1421 (2015).

Hare, M. J., Shaw, J. E. & Zimmet, P. Z. Current controversies in the use of haemoglobin A1c. J. Intern. Med. 271, 227–236 (2012).

Lacy, M. E. et al. Association of sickle cell trait with hemoglobin A1c in African Americans. JAMA 317, 507–515 (2017).

Piel, F. B. et al. The distribution of haemoglobin C and its prevalence in newborns in Africa. Sci. Rep. 3, 1671 (2013).

Piel, F. B. et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 381, 142–151 (2013).

Beutler, E. & West, C. Hematologic differences between African-Americans and whites: the roles of iron deficiency and α-thalassemia on hemoglobin levels and mean corpuscular volume. Blood 106, 740–745 (2005).

Mei, Z. et al. Assessment of iron status in US pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93, 1312–1320 (2011).

Hanchard, N. A., Hambleton, I., Harding, R. M. & McKenzie, C. A. The frequency of the sickle allele in Jamaica has not declined over the last 22 years. Br. J. Haematol. 130, 939–942 (2005).

Modell, B. & Darlison, M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull. World Health Organ. 86, 480–487 (2008).

Taylor, C., Kavanagh, P. & Zuckerman, B. Sickle cell trait — neglected opportunities in the era of genomic medicine. JAMA 311, 1495–1496 (2014).

Danese, E., Montagnana, M., Nouvenne, A. & Lippi, G. Advantages and pitfalls of fructosamine and glycated albumin in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 9, 169–176 (2015).

Hsu, P. et al. A comparison of glycated albumin and glycosylated hemoglobin for the screening of diabetes mellitus in Taiwan. Atherosclerosis 242, 327–333 (2015).

Ikezaki, H. et al. Glycated albumin as a diagnostic tool for diabetes in a general Japanese population. Metabolism 64, 698–705 (2015).

Shima, K., Abe, F., Chikakiyo, H. & Ito, N. The relative value of glycated albumin, hemoglobin A1c and fructosamine when screening for diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 7, 243–250 (1989).

Wu, W. C. et al. Serum glycated albumin to guide the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 11, e0146780 (2016).

Chan, C. L. et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in obese youth: evaluating alternate markers of glycemia — 1,5-anhydroglucitol, fructosamine, and glycated albumin. Pediatr. Diabetes 17, 206–211 (2015).

Sumner, A. E. et al. A1C combined with glycated albumin improves detection of prediabetes in Africans: the Africans in America Study. Diabetes Care 39, 271–277 (2016).

Selvin, E. et al. Fructosamine and glycated albumin for risk stratification and prediction of incident diabetes and microvascular complications: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2, 279–288 (2014).

Sumner, A. E. et al. Glycated albumin identifies prediabetes not detected by hemoglobin A1c: the Africans in America Study. Clin. Chem. 62, 1524–1532 (2016).

Koga, M., Hirata, T., Kasayama, S., Ishizaka, Y. & Yamakado, M. Body mass index negatively regulates glycated albumin through insulin secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 438, 19–23 (2015).

Koga, M., Matsumoto, S., Saito, H. & Kasayama, S. Body mass index negatively influences glycated albumin, but not glycated hemoglobin, in diabetic patients. Endocr. J. 53, 387–391 (2006).

Koga, M. et al. Negative association of obesity and its related chronic inflammation with serum glycated albumin but not glycated hemoglobin levels. Clin. Chim. Acta 378, 48–52 (2007).

Prasad, R. B. & Groop, L. Genetics of type 2 diabetes-pitfalls and possibilities. Genes (Basel) 6, 87–123 (2015).

Ng, M. C. Genetics of type 2 diabetes in African Americans. Curr. Diab. Rep. 15, 74 (2015).

Fuchsberger, C. et al. The genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. Nature 536, 41–47 (2016).

Lettre, G. et al. Genome-wide association study of coronary heart disease and its risk factors in 8,090 African Americans: the NHLBI CARe Project. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001300 (2011).

Ng, M. C. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in African Americans provides insights into the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004517 (2014).

Palmer, N. D. et al. A genome-wide association search for type 2 diabetes genes in African Americans. PLoS ONE 7, e29202 (2012).

Saxena, R. et al. Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 39 studies identifies type 2 diabetes loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 410–425 (2012).

Wessel, J. et al. Low-frequency and rare exome chip variants associate with fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 6, 5897 (2015).

Dooley, J. et al. Genetic predisposition for beta cell fragility underlies type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet. 48, 519–527 (2016).

Narimatsu, H. Gene-environment interactions in preventive medicine: current status and expectations for the future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E302 (2017).

Adeleye, J. O. & Abbiyesuku, F. M. Glucose and insulin responses in offspring of Nigerian type 2 diabetics. Afr. J. Med. Med. Sci. 31, 253–257 (2002).

Erasmus, R. T. et al. Importance of family history in type 2 black South African diabetic patients. Postgrad. Med. J. 77, 323–325 (2001).

Goldfine, A. B. et al. Insulin resistance is a poor predictor of type 2 diabetes in individuals with no family history of disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2724–2729 (2003).

Mbanya, J. C., Pani, L. N., Mbanya, D. N., Sobngwi, E. & Ngogang, J. Reduced insulin secretion in offspring of African type 2 diabetic parents. Diabetes Care 23, 1761–1765 (2000).

Rotimi, C., Cooper, R., Cao, G., Sundarum, C. & McGee, D. Familial aggregation of cardiovascular diseases in African-American pedigrees. Genet. Epidemiol. 11, 397–407 (1994).

Haupt, A. et al. Gene variants of TCF7L2 influence weight loss and body composition during lifestyle intervention in a population at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 59, 747–750 (2010).

Kilpelainen, T. O. et al. SNPs in PPARG associate with type 2 diabetes and interact with physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40, 25–33 (2008).

Reinehr, T. et al. Evidence for an influence of TCF7L2 polymorphism rs7903146 on insulin resistance and sensitivity indices in overweight children and adolescents during a lifestyle intervention. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 32, 1521–1524 (2008).

Ruchat, S. M. et al. Improvements in glucose homeostasis in response to regular exercise are influenced by the PPARG Pro12Ala variant: results from the HERITAGE Family Study. Diabetologia 53, 679–689 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Variants of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene predict conversion to type 2 diabetes in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study and are associated with impaired glucose regulation and impaired insulin secretion. Diabetologia 50, 1192–1200 (2007).

Botden, I. P. et al. Variants in the SIRT1 gene may affect diabetes risk in interaction with prenatal exposure to famine. Diabetes Care 35, 424–426 (2012).

Corella, D. et al. CLOCK gene variation is associated with incidence of type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases in type-2 diabetic subjects: dietary modulation in the PREDIMED randomized trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 15, 4 (2016).

Cornelis, M. C. et al. Joint effects of common genetic variants on the risk for type 2 diabetes in U.S. men and women of European ancestry. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 541–550 (2009).

de Rooij, S. R. et al. The effects of the Pro12Ala polymorphism of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ2 gene on glucose/insulin metabolism interact with prenatal exposure to famine. Diabetes Care 29, 1052–1057 (2006).

Ericson, U. et al. Sex-specific interactions between the IRS1 polymorphism and intakes of carbohydrates and fat on incident type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 208–216 (2013).

Hindy, G. et al. Role of TCF7L2 risk variant and dietary fibre intake on incident type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 2646–2654 (2012).

Lamri, A. et al. Dietary fat intake and polymorphisms at the PPARG locus modulate BMI and type 2 diabetes risk in the D.E.S.I.R. prospective study. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 36, 218–224 (2012).

Sonestedt, E. et al. Genetic variation in the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor modifies the association between carbohydrate and fat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in the Malmo Diet and Cancer cohort. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E810–E818 (2012).

van Hoek, M., Langendonk, J. G., de Rooij, S. R., Sijbrands, E. J. & Roseboom, T. J. Genetic variant in the IGF2BP2 gene may interact with fetal malnutrition to affect glucose metabolism. Diabetes 58, 1440–1444 (2009).

Villegas, R., Goodloe, R. J., McClellan, B. E. Jr, Boston, J. & Crawford, D. C. Gene–carbohydrate and gene–fiber interactions and type 2 diabetes in diverse populations from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) as part of the Epidemiologic Architecture for Genes Linked to Environment (EAGLE) study. BMC Genet. 15, 69 (2014).

Sterns, J. D., Smith, C. B., Steele, J. R., Stevenson, K. L. & Gallicano, G. I. Epigenetics and type II diabetes mellitus: underlying mechanisms of prenatal predisposition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2, 15 (2014).

Bramswig, N. C. & Kaestner, K. H. Epigenetics and diabetes treatment: an unrealized promise? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 23, 286–291 (2012).

Waterland, R. A. et al. Season of conception in rural gambia affects DNA methylation at putative human metastable epialleles. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001252 (2010).

Ramsay, M. & Sankoh, O. African partnerships through the H3Africa Consortium bring a genomic dimension to longitudinal population studies on the continent. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 305–308 (2016).

Marin, C. & Brunel, S. A continent exhausted by war and famine. Le Monde diplomatique http://mondediplo.com/maps/africamdv49 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities and the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health (CRGGH) (grant 1ZIAHG200362). The CRGGH is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Center for Information Technology and the Office of the Director at the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.E.S. researched data for the article. J.N.U., S.T.C., A.R.B., M.U. and A.E.S. made substantial contributions to discussion of the content, wrote the article and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission. J.N.U. and S.T.C. contributed equally to the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Supplementary information

Supplementary information S1 (table)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus loci with evidence in individuals of African ancestry (PDF 105 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Utumatwishima, J., Chung, S., Bentley, A. et al. Reversing the tide — diagnosis and prevention of T2DM in populations of African descent. Nat Rev Endocrinol 14, 45–56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.127

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.127

This article is cited by

-

Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes in sub-Saharan Africans

Diabetologia (2022)

-

Biology of aging: Oxidative stress and RNA oxidation

Molecular Biology Reports (2022)

-

Current perspectives on the clinical implications of oxidative RNA damage in aging research: challenges and opportunities

GeroScience (2021)

-

Treating T2DM by ensuring insulin access is a global challenge

Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2019)

-

Dysregulated expression of long noncoding RNAs serves as diagnostic biomarkers of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Endocrine (2019)